SPLC grants support organizations that seek to remove Confederate symbols

Once a month, members of the Committee for Justice, Equality and Fairness (CJEF) meet in the small back room of Sandra Macon’s church to discuss what to do about the problem at the Walton County Courthouse in DeFuniak Springs, Florida.

Just outside the courthouse stands a marble pillar erected in honor of “Walton County’s Confederate dead,” and flying just beside it is a Confederate flag. Macon, a retired U.S. Army veteran who was born and raised in DeFuniak Springs, passes by it every day.

“It’s a slap in the face,” Macon said. “Like a wound that’s been rubbed with salt.”

Macon, 66, was born during Jim Crow, just as the modern Civil Rights Movement was gaining steam. She remembers the segregated – then integrated – schools she attended in the Florida Panhandle town, where about 7,000 people live today. She recalls how her family entered restaurants and businesses through back doors and how the railroad tracks that bisect Baldwin Avenue divided the town’s Black and white neighborhoods.

For Macon and the members of CJEF, there is no honor in what these Confederate symbols represent. Last year, the group received a grant from the Southern Poverty Law Center to aid its effort to remove the flag and relocate the monument.

“The SPLC was of the first groups to offer us support and guidance,” said CJEF co-founder Mike Bowden. “Our work with them has really been wonderful for us. It’s a lonely business doing this committee work. We don’t have much in the way of tangible results, but we continue to pledge ourselves not to give up on this effort. So, it’s really great to have the SPLC on our side.”

The grant was one of eight awarded by the SPLC’s Intelligence Project to support grassroots advocates who are working to remove Confederate monuments and other iconography from public spaces in their communities.

Bowden said the grant has helped the group draw attention to the campaign on social media and in the traditional media. CJEF is also working with E Pluribus Unum to develop messaging and strategy. E Pluribus Unum was founded by former New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu, who gained national prominence for removing four Confederate monuments in his city.

“Powerful, transformative change happens when communities organize together around their own needs,” said Rivka Maizlish, a historian and senior research analyst for the Intelligence Project. “Through this pilot project, the SPLC is funding grassroots organizations working to remove Confederate symbols that perpetuate the ‘Lost Cause’ myth and glorify the Confederacy as a noble cause. These groups are inspiring examples of advocates who are pushing for and often achieving lasting change.”

In addition to CJEF, the recipients of the pilot grants include Take ‘Em Down Jax, in Jacksonville, Florida; the Stone Mountain Action Coalition in Atlanta; Ghosts of a Lost Cause, a film about the effort to remove a memorial to Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee in Murray, Kentucky; Project Say Something in Florence, Alabama; the North Carolina Commission on Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Criminal Justice System in Durham; Change Our Name Fort Bragg in Fort Bragg, California; and the Northside Coalition of Jacksonville in Florida.

A political act

The monument at the Walton County Courthouse was the first Confederate memorial to be erected in Florida after the Civil War. It was installed in the cemetery of a local Presbyterian church in 1871 and later moved to the town of Eucheeanna, the county seat. When DeFuniak Springs became the county seat in 1886, the monument was moved to the courthouse.

The flag at the courthouse was first flown in 1964, as segregationists were pushing back against the Civil Rights Movement, installing hundreds of Confederate flags and monuments in public spaces across the South. Today, more than 2,000 of these memorials and other symbols still exist across the U.S., as documented by the SPLC’s Whose Heritage? initiative. The project – sparked by the 2015 murder of nine Black worshipers by a white supremacist gunman at the “Mother Emanuel” AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina – tracks and contextualizes publicly displayed symbols of the Confederacy and provides communities with resources to aid in their efforts to remove them.

Since 2015, advocates have successfully removed, renamed or relocated 377 Confederate monuments and symbols from communities across the country. One month after the 2015 Charleston massacre, community members successfully pushed South Carolina legislators to remove the Confederate flag that had flown at the statehouse since 1962. Five more flags have been removed in different states since then. In Florida, 77 of these symbols remain in public spaces – two of them Confederate flags, flown in Walton and Marion counties.

“Clearly the flag was erected in 1964 to push back on the Civil Rights Act,” said Bowden. “The monument goes back much further than that, having been erected shortly after the Civil War. Having it moved to the courthouse is a political statement. It’s an act that claims the courthouse as white territory, that this is an area that belongs to us, and we’re laying claim to it by putting our monument to those who fought to maintain slavery on the courthouse property.

“We don’t want a monument to that history to be placed on public property. It belongs in a museum or in a cemetery.”

Bowden, who is originally from Michigan, moved to Walton County on the heels of former President Donald Trump’s election. As Trump’s xenophobic rhetoric further polarized the nation, he and his wife, Susan, looked to connect with like-minded community members. They joined a 2017 campaign to petition county commissioners to remove the flag. In 2018, the commissioners put the question to residents in a nonbinding referendum, but 65% of voters opted to keep the flag. The Bowdens decided to continue the fight alongside some of the former petitioners. CJEF blossomed from that effort.

Pushing forward

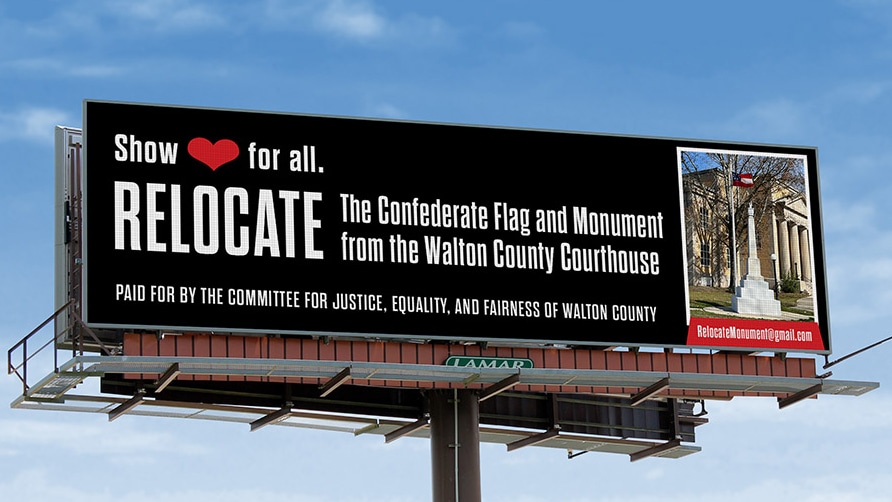

The SPLC’s grant could not have come at a better time. As with many grassroots initiatives, funding can be a major challenge. The SPLC grant helped CJEF launch a public awareness campaign that includes three digital billboards at key junctions throughout the county.

The idea is to apply economic pressure on the county by appealing to tourists who flock to the county’s beaches during summer months. About 30 miles from Florida’s Gulf Coast, DeFuniak Springs is a main gateway to the destination. In 2022, tourists accounted for 76% of the county’s retail spending, according to its most recent annual report. That year, more than 5.3 million visitors contributed almost $5 billion in direct spending to the economy.

While the group said that its letters and calls to county officials often go unanswered, it believes that threatening the county’s dollars may get their attention.

“Our hope was that posting a billboard would have some economic impact – that people who came would recognize that was part of what Walton County is about and choose to spend their vacation dollars elsewhere,” Bowden said. “It’s a little early to tell whether that will happen.”

Their attempts to get the Walton County Chamber of Commerce on board have yielded mixed results.

When CJEF’s vice chair, Drexel Harris, wrote in a letter to the chamber that it was listed as a sponsor of the monument on the county’s website, its name was quickly removed from the site. Yet the chamber has not agreed to support the removal of the monument and flag.

“This is a conservative area,” Harris said. “Some Republican state legislators are trying to pass a bill to make it illegal for anybody to remove a Confederate monument,” as Alabama, Georgia and Tennessee have done.

Despite these obstacles, CJEF members remain resolute in their fight against the celebration of the Confederacy and white supremacy.

“They want us to shut up and leave this alone,” said Macon, the retired U.S. Army veteran. “But we won’t stop coming.”

Image at top: Drexel Harris, co-chair of the Committee for Justice, Equality and Fairness (CJEF); Susan Bowden, a CJEF founding member; Kimberly Allen, senior media strategist for the Southern Poverty Law Center; Mike Bowden, CJEF co-founder and co-chair; and Shauna Lewis, community engagement manager for E Pluribus Unum. (Courtesy of CJEF)