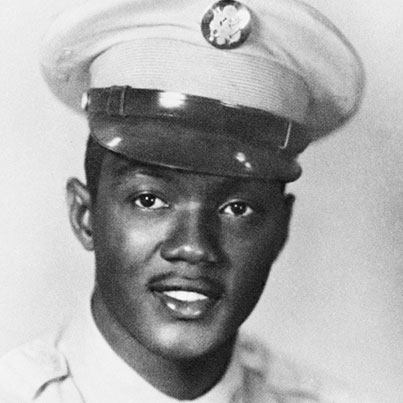

His mother worried endlessly, but Oneal Moore could not have been prouder when he was chosen to be one of the first black deputies in Washington Parish, La.

His selection was no surprise to those who knew him. Moore was a 34-year-old Army veteran who had distinguished himself as a leader in his church, his local fraternal lodge and the PTA. He had four daughters who idolized him and a wife who had great ambitions for him and their children. Another black man, Creed Rogers, was also named as a deputy.

Moore knew he had put himself and his family at risk by accepting the job, and he tried to be cautious. While other black residents marched and picketed, Moore avoided civil rights activities. He wanted only to be able to perform his duty as an officer.

Exactly a year after they were appointed – June 2, 1965 – Rogers and Moore were heading home when their car was hit by gunfire. Moore was hit in the head and instantly killed. Rogers was wounded in the shoulder and blinded in one eye. He managed to broadcast a description of the vehicle on the police radio – a black pickup truck with a Confederate flag decal on the front bumper.

No one was ever convicted in the shooting. The prime suspect in the case died in 2003.

Despite the rage that many black people felt at the murder of Oneal Moore, Maevella Moore would allow no signs of anger at her husband’s funeral. A New York Times reporter described the eulogy as “remarkably free of bitterness.”

After Moore’s death, boycotts finally succeeded in forcing the integration of restaurants and theaters in the Washington Parish town of Bogalusa. Rural black youths began learning about their rights at Freedom Schools run by the Congress of Racial Equality. A massive voter registration drive added hundreds of black people to the voting rolls.